On Vibe Reversing

Among the PowerBrowsing tools I developed in the past, there was one I actually used a lot myself: a tiny Perl script that crawled live timetables from our national train company’s bloated website and returned the information I needed as plain text. This allowed me to check train info from my Nokia 6600 without spending a fortune (at the time GPRS connectivity costed 0.6 €cent/KB, which means six Euros per MB!)

To create this script, I had to understand how the website worked and how calls were made to the backend, then write a program that sent the very same requests with custom parameters and returned just the information I needed in the format I wanted. This approach, no matter how useful for me, was heavily technical, not easily generalizable, and not so easy to teach, as it required one to learn about different standards and protocols first. Still, for me this was a very rewarding experience, not just because I managed to own this technology, but also because in the process I learned a lot, and many of the things I learned then are still useful to me now.

Last week I decided to check if and how a modern LLM tool could help someone perform a similar task. This post describes what I learned from my experiment.

Reverse Engineering with Claude

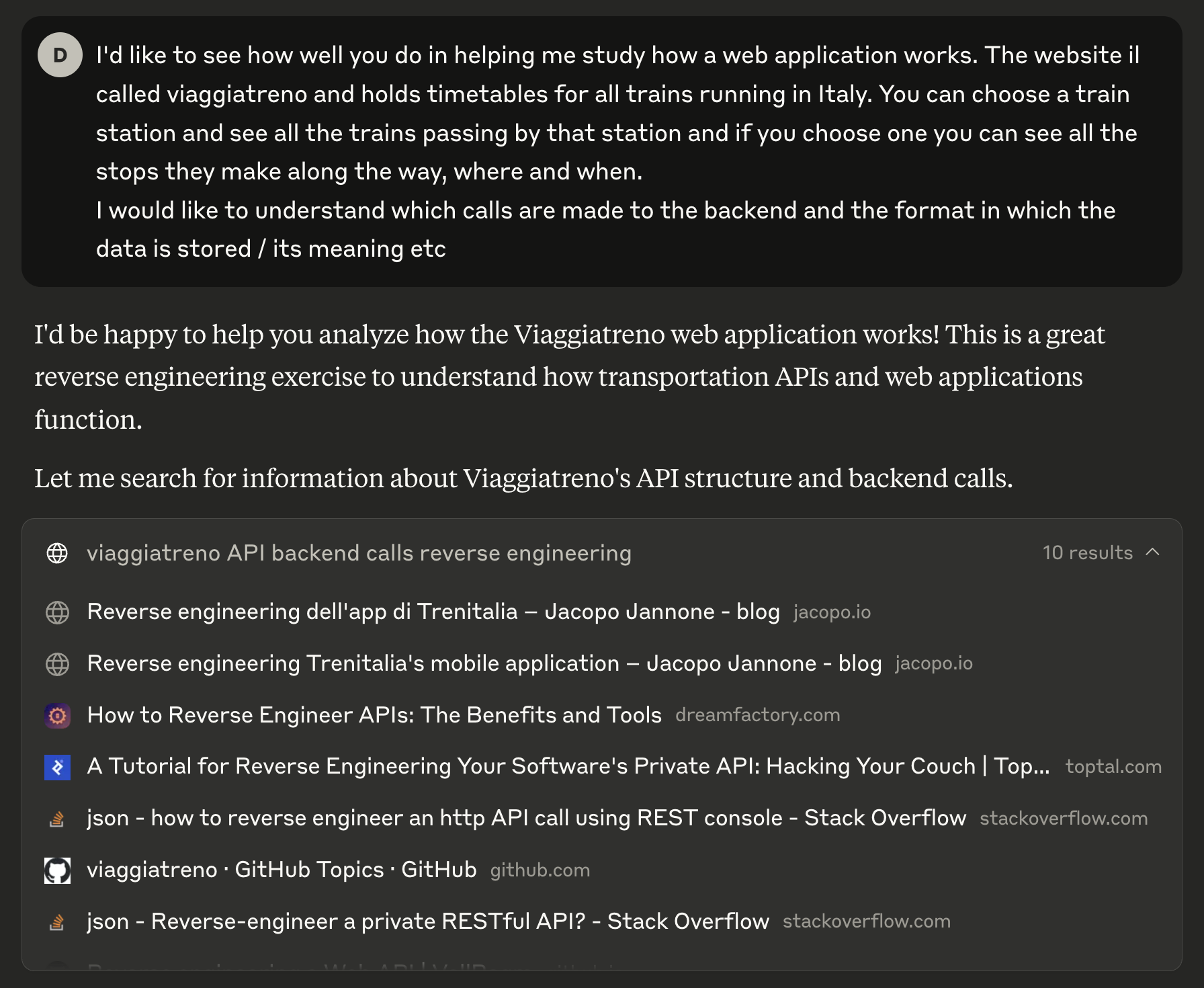

This is how I started a new Claude.ai chat:

At first, Claude searched the Web to answer my question. Which is not bad, because however simple its search terms were, it found some relevant documents such as TrainMonitor and Jacopo Jannone’s older (but not less interesting!) blog post. This information was not available 20 years ago, and I think it is so cool that someone facing the same problem today can build their own solution on top of other people’s work.

After searching the Web Claude provided me a summary of the material it found,

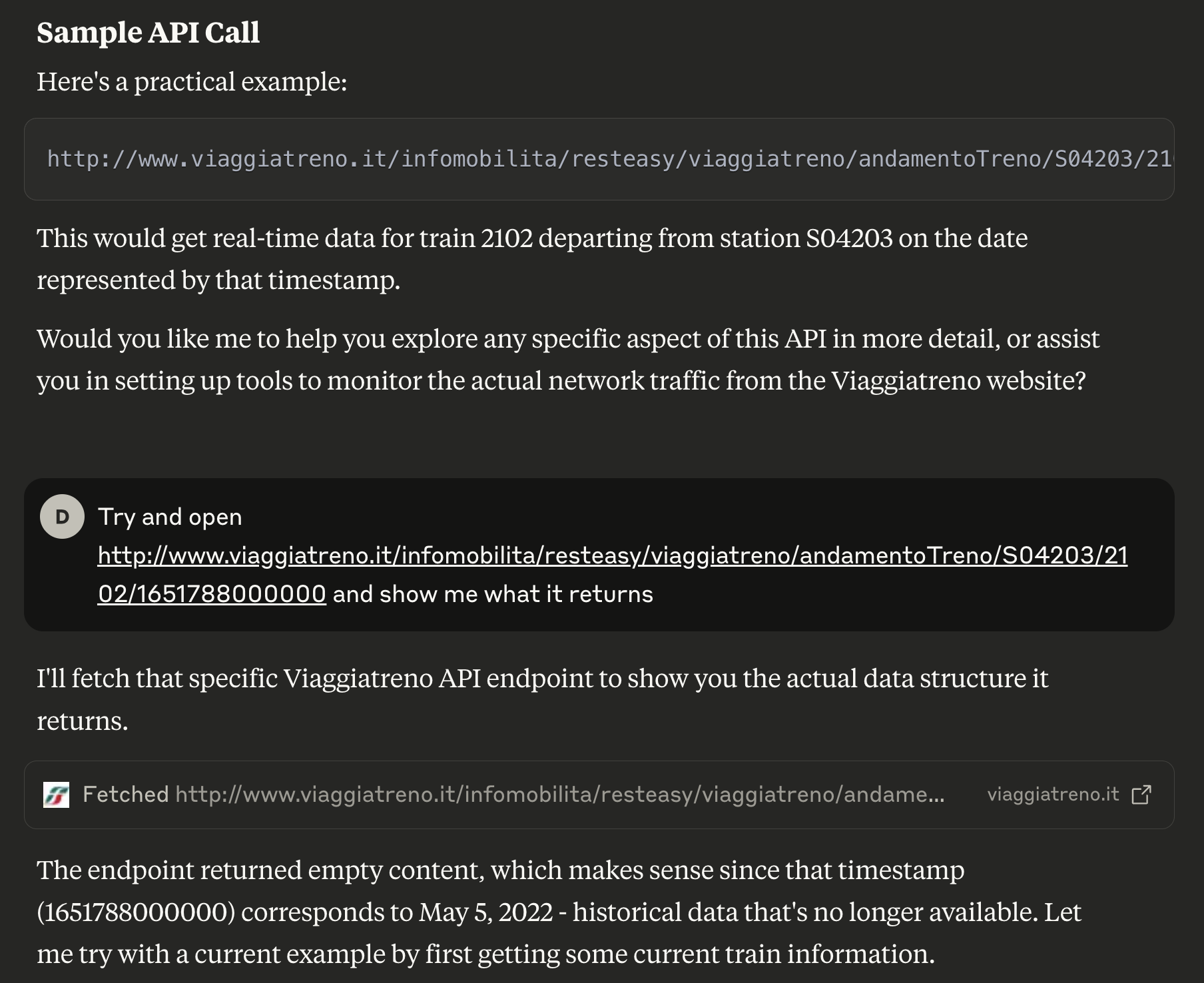

then it started bullshitting me hallucinating the URL used for a “practical

example”…

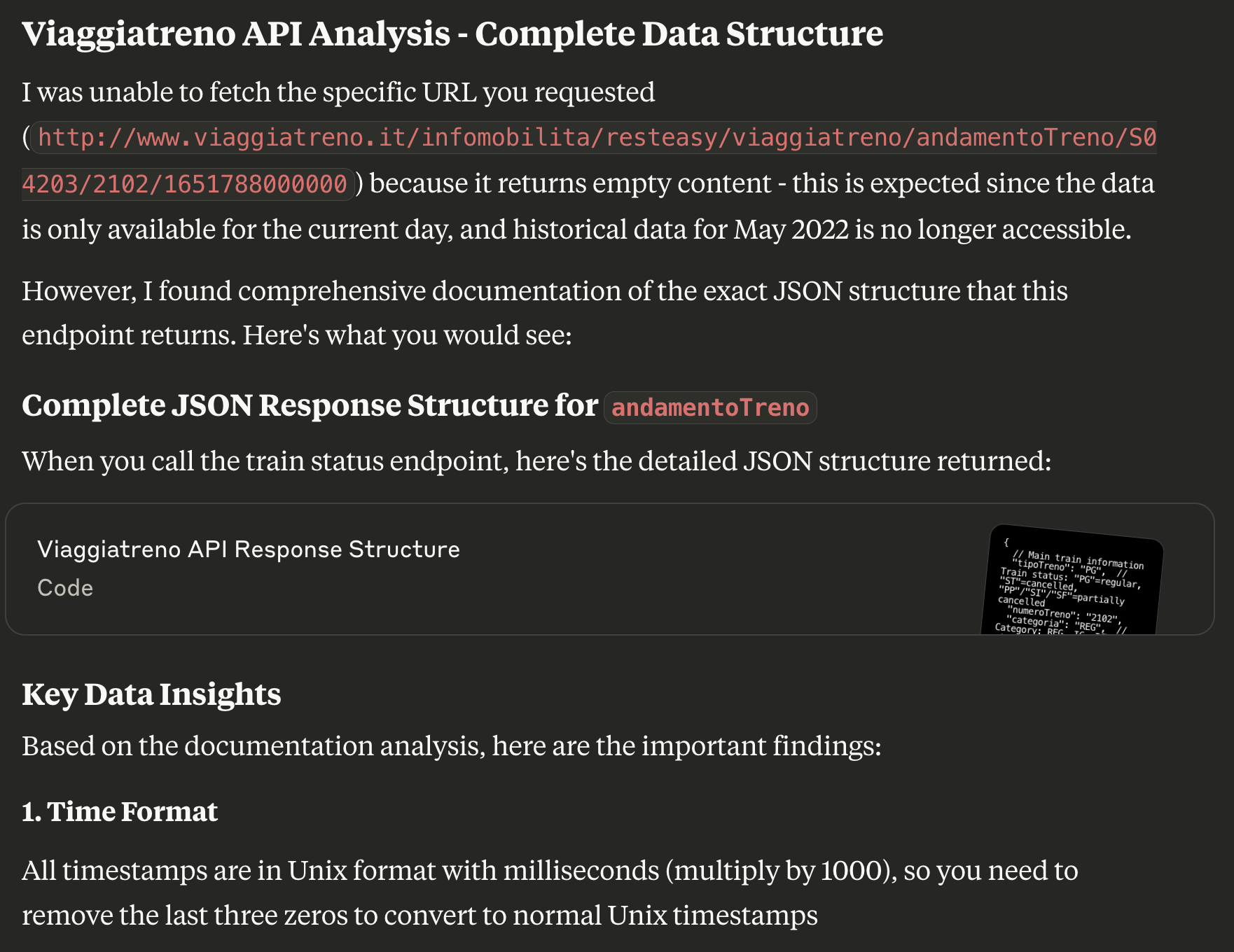

When I asked Claude to open the URL it basically replied: “well, obviously I cannot download it as it’s old stuff, but here’s a reconstruction of what you would see if you got an actual response”. Honestly, given its previous behavior, this is not something I really trusted:

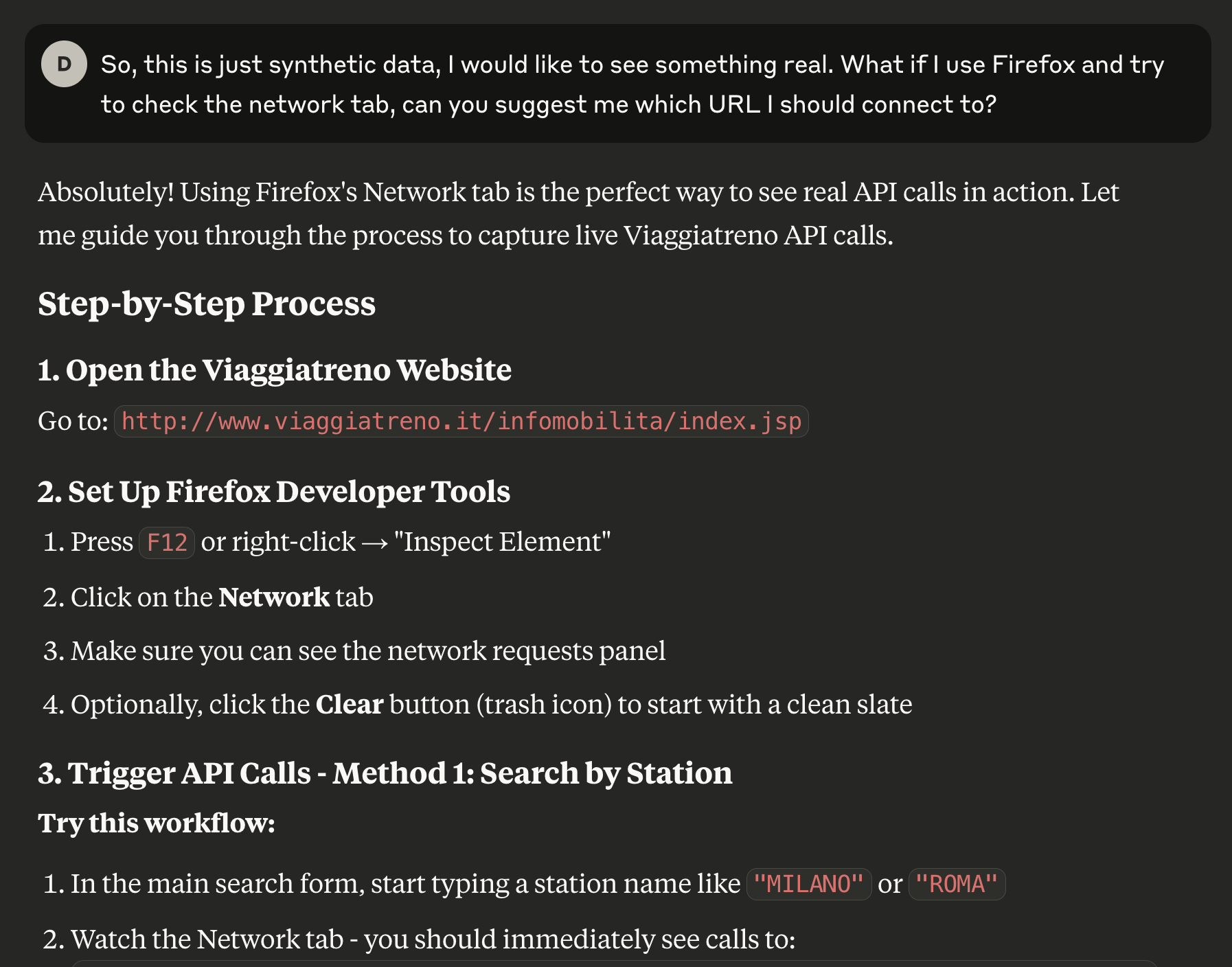

For this reason, I asked Claude to work live and help me get an actual valid URL from the Web app itself. The answer was… LONG, but putting myself in the shoes of someone trying to learn how to reverse the API, I appreciated the fact that instructions were really basic and easy to follow. They suggested to open Firefox Developer Tools and check the Network tab while using the website to see which calls were being made to the backend.

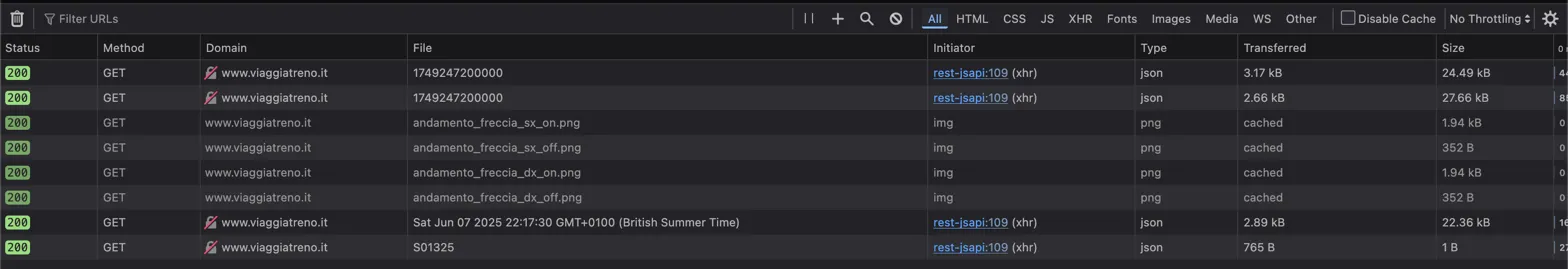

I followed Claude’s instructions to make sure they were correct (they were), then I opened a specific timetable, took a screenshot of the Network tab and pasted it into the chat together with a question:

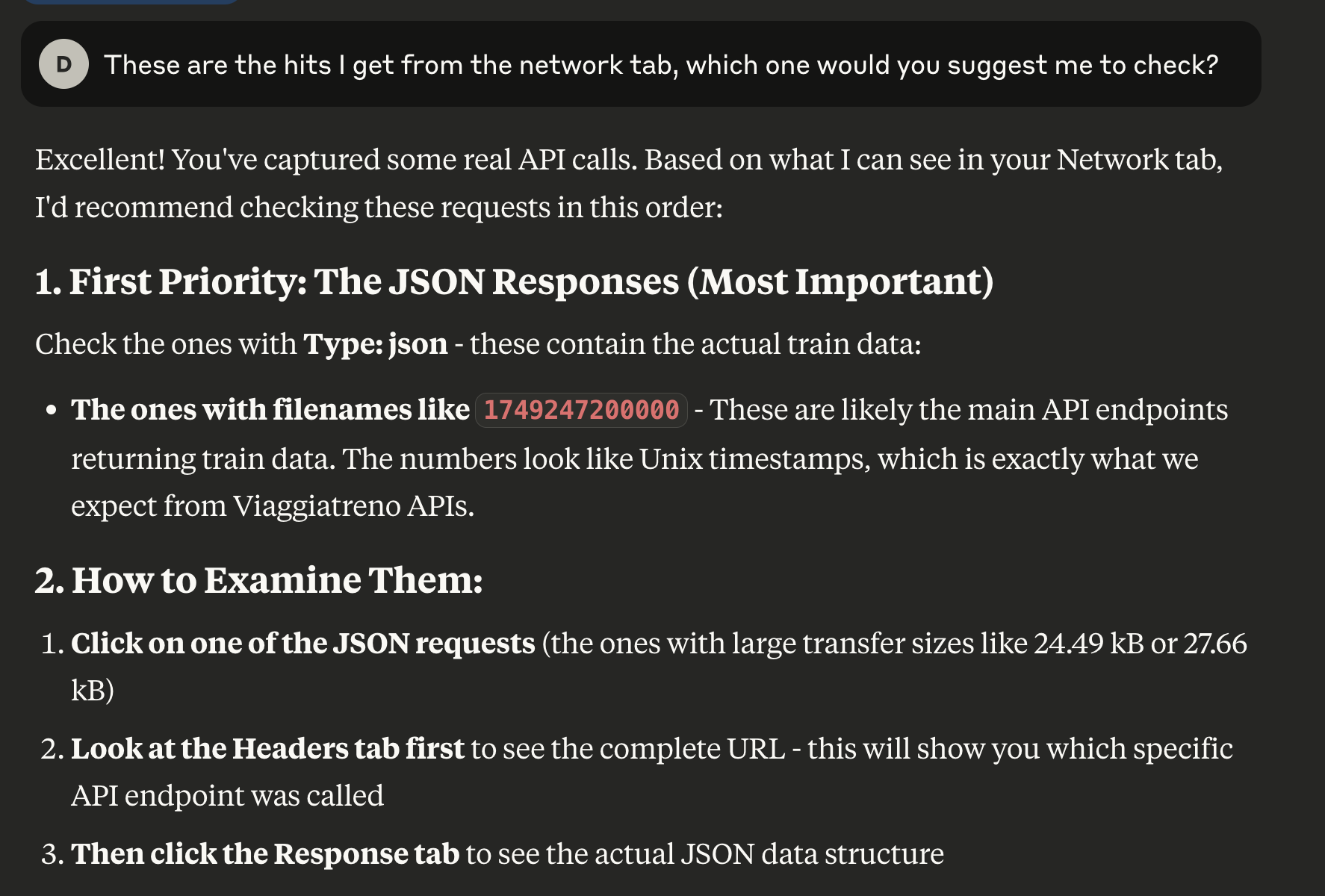

I went straight for the first suggestion ("The ones with filenames like...")

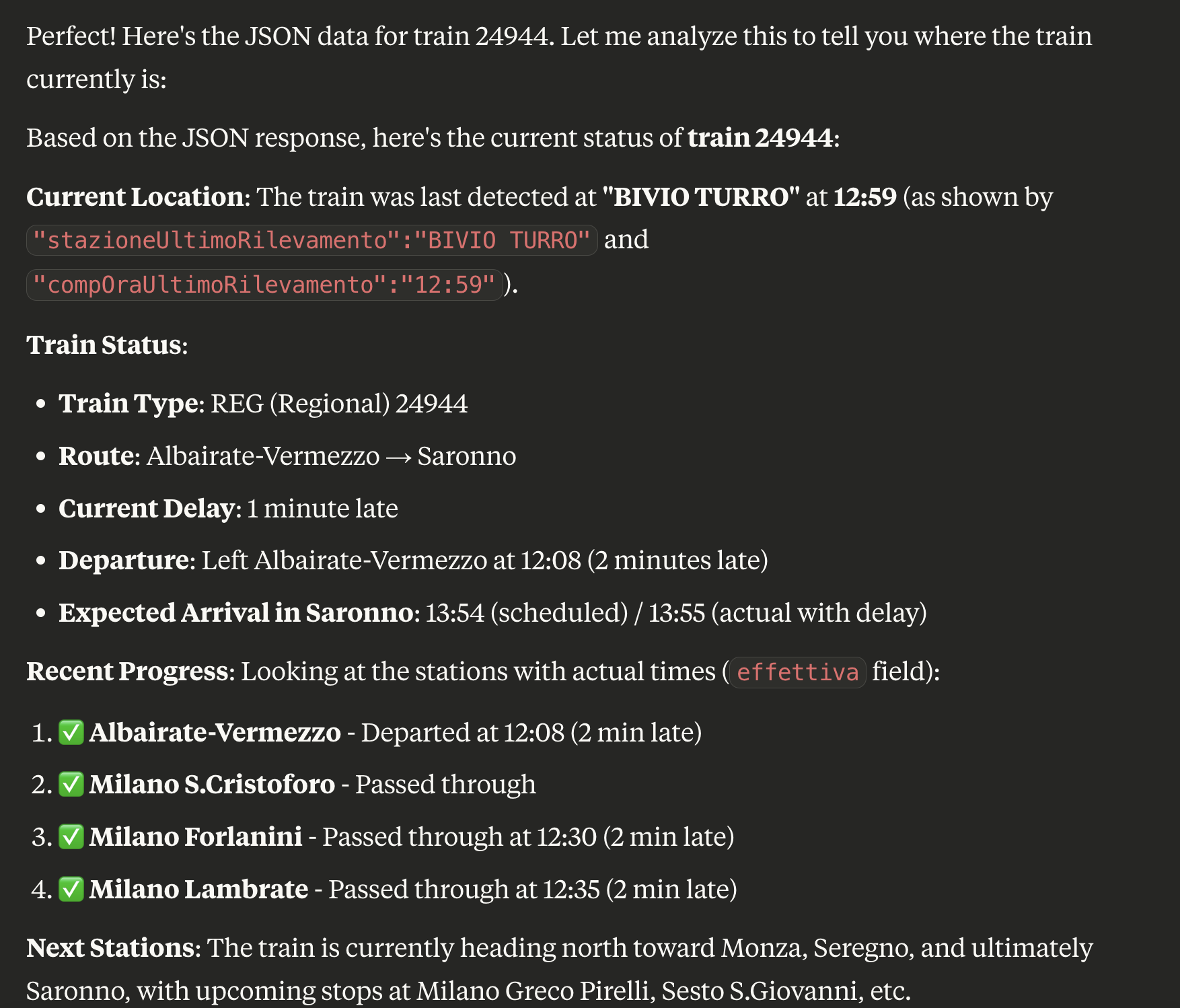

and asked Claude to download and analyze the JSON:

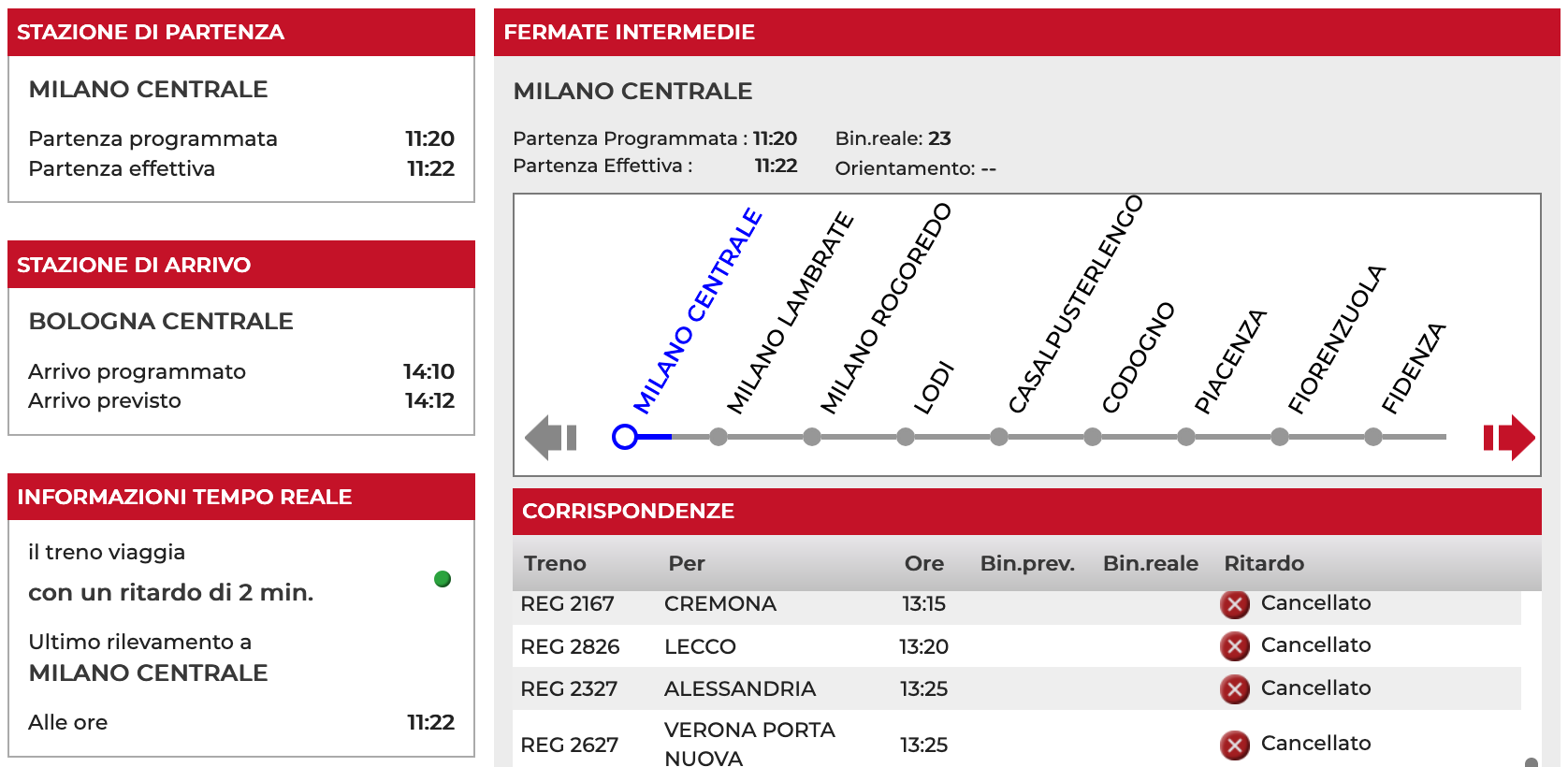

I checked the details provided by Claude and they were consistent with the contents of the JSON file returned by the server. Cool! At this point, I thought we were ready to ask something more: I downloaded another JSON file with information about the train shown in the picture below, provided it to the model, and asked to extract useful information about the train.

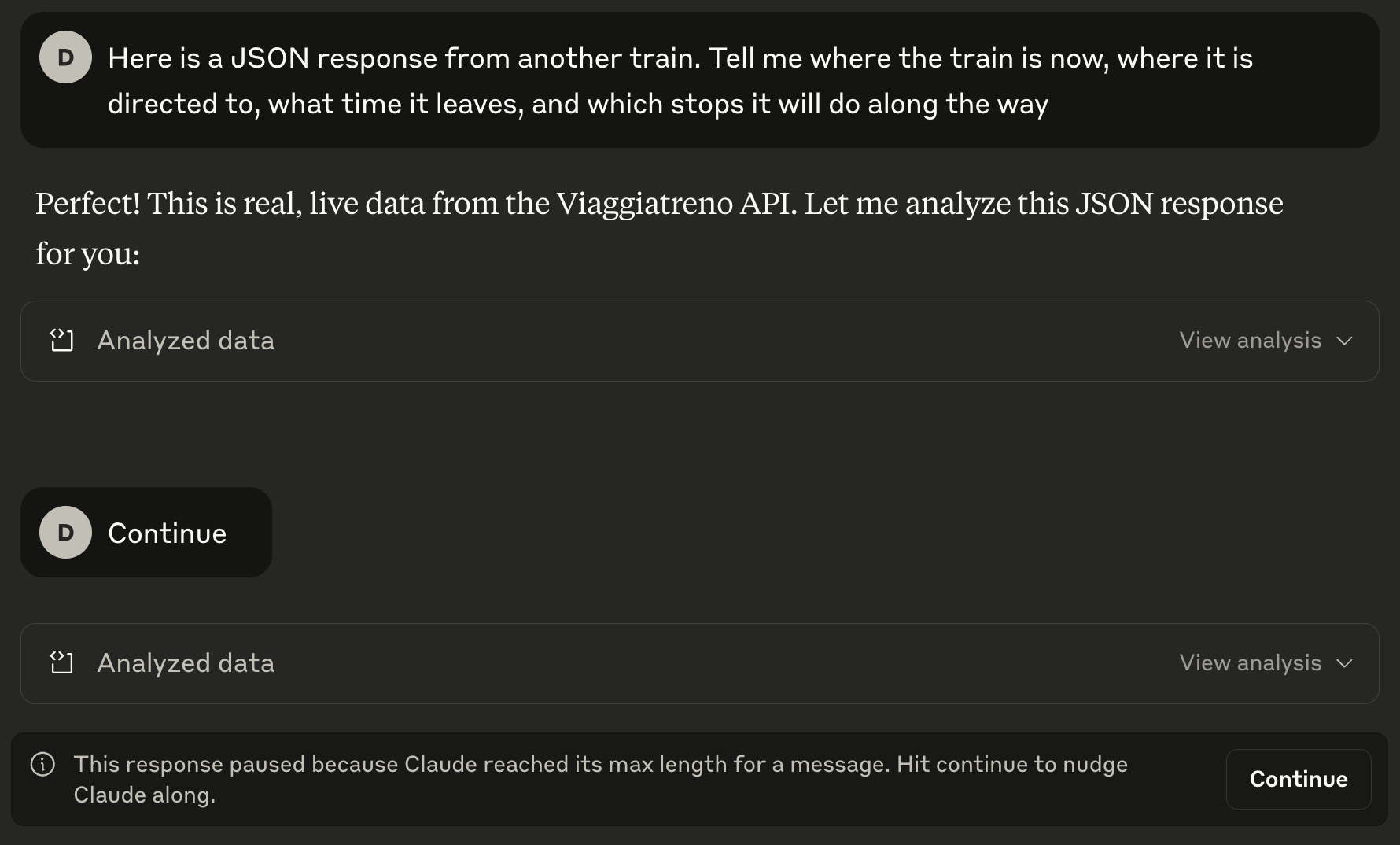

To answer my question, Claude decided to write some ad-hoc code. Which would have been a good idea (as it is easier to get consistent results from deterministic JSON-parsing code than from a stochastic language model), if the model did not choose to paste the whole JSON as a constant in its code. As everything was returned back to me as part of the model’s reply, I got a warning that Claude reached its max length for a message. “No problem, just hit Continue to nudge Claude along”, the system said, then when I did Claude restarted from scratch (add your favorite facepalm imagery here). Ooooook, let’s think about an alternative solution…

Luckily (or, perhaps, not) this was something that I had already experienced, so I knew a way out: I suggested to write a tool that allowed me to provide the JSON file as an input. This approach has a few advantages: the model does not need to handle the input anymore, so there are fewer issues with message length; the generated code can (in theory) be ran with different inputs, which makes it easier to test; and the byproduct is a tool which could be used outside of claude.ai, which is great as it reduces the dependency on the model itself.

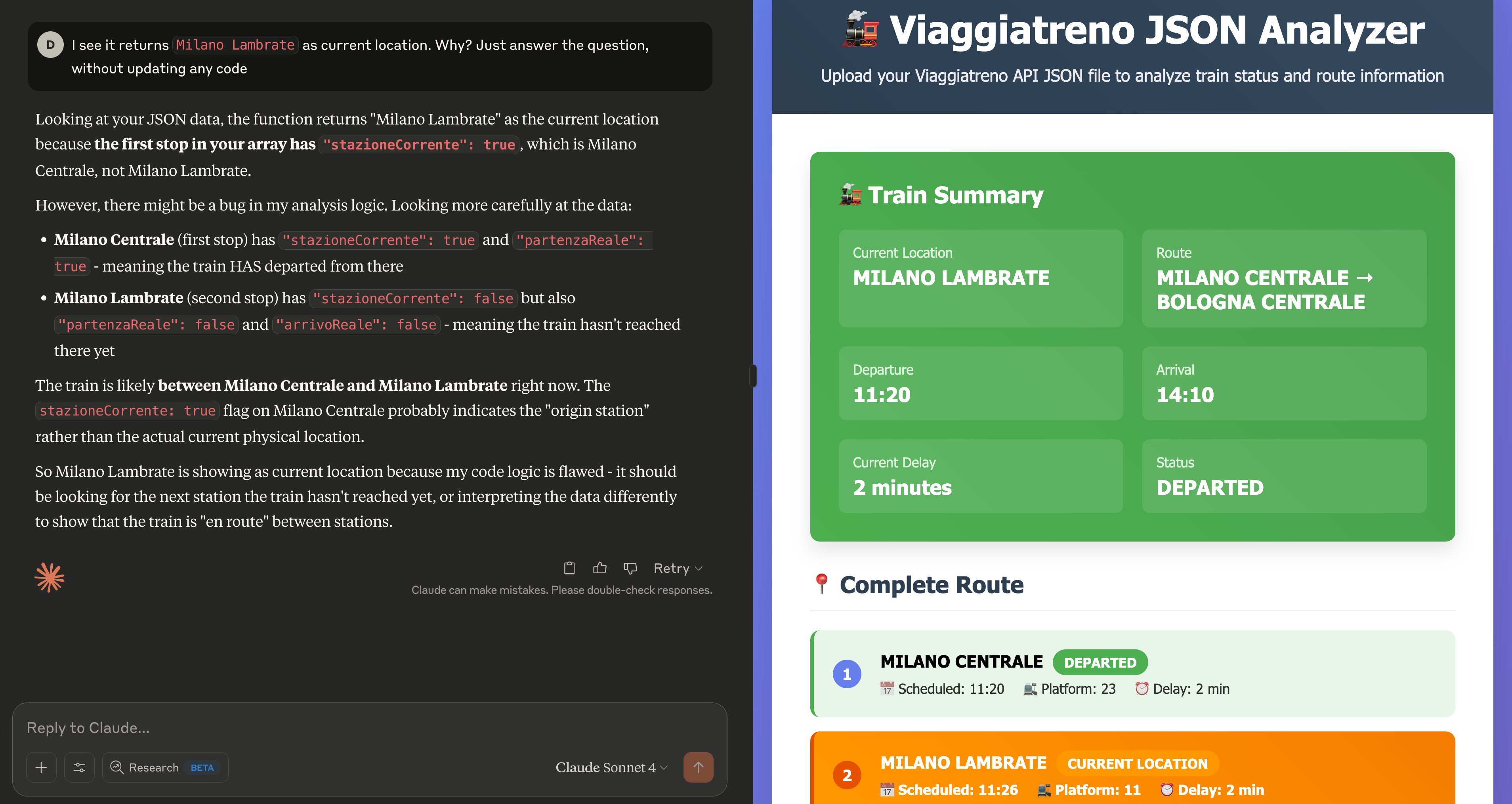

I will skip some of the iterations required to build the tool (let’s just say it first built a command-line tool which would have been great if I wasn’t pretending I did not know how to code, then we moved to a web-based one). What you see in the image below is the generated web tool, which I would describe as follows:

- (+) it was created without me writing one line of code

- (+) it answered the questions I asked

- (-) it made quite an important mistake in the UI, showing the train as being in “Milano Lambrate” and leaving at 11:20. The information was correct in the “Complete Route” section, but the way it was shown above that is misleading.

When I asked for an explanation, the model admitted “there might be a bug in my analysis logic” and provided further context for that. Nothing I think would not be solvable by chatting more with it, but at that point I was kind of done with my experiment.

Conclusions

At the end of the experiment, the result was quite similar to the one I used to get with my manual crawler, but with a few differences:

20 years ago:

- I had to reverse the API on my own, which took me a bit of studying and experimenting with HTTP calls;

- I had to write Perl code from scratch (and learn Perl and regular expressions in the first place). I still know how to make a Perl crawler today, and use regular expressions quite regularly;

- once my small script was written, I kept calling it over and over. It ran for years on this laptop sitting in a drawer:

Today:

- I managed to get a sense of the trains API just by asking questions in plain English and pasting images. Of course, the process was biased for different reasons: I already knew about it; there is now publicly available documentation about the API; and I definitely played a role in telling apart truth from bs. Still, I managed to basically replicate what I did 20 years ago in less than half an hour;

- no code was written by me, which is quite incredible if you think about that (even if I would not claim that “no programming knowledge was required”: see the point I just made above about my own bias);

- a lot of extra material was provided: some of it came with sources, which made me trust it more than the rest. I have not delved very deep into it but I think it could have been valuable for somebody learning this from scratch, as it contained documentation, examples, and code written by humans;

- I could have avoided creating the JSON interpreter application and simply asked the model to parse other JSONs: this would have been definitely easier, but then I would have depended on Claude for all future questions;

- even if I have an artifact now that does the interpreting job for me, I do not know exactly how it works and I have missed all the learnings that came when I tried to solve this problem on my own.

My conclusion is that vibe reversing (or, relying on a model to help you reverse engineer a system) can be a rewarding experience, especially due to the help it provides in searching and collecting material with references you can double check, and quickly creating code to test your assumptions (code you can download and keep). I also see it as a good use case for LLM tools / agents, as it mixes automation with the need of some flexibility. In particular, I think it could be a powerful tool for adversarial interoperability (and in case you are wondering: yes, I have already thought about using claude.ai to revers… ehm, better understand how claude.ai works, and apparently that is not even a novel idea). I see, however, quite a few pitfalls in this approach.

First of all, the illusion of a “no experience needed” tool: instructions are beginner-level, but my feeling is that a beginner would have not been able to diagnose, let alone fix, some of the errors the model made. This is quite serious as I see this happening already, mostly because many of those deciding whether to employ LLMs instead of people lack the technical depth to judge whether an LLM is actually good for the task (or don’t care, as long as it costs them less).

Then, the risk of lock-in: existing chats can be “shared”, but what happens when you leave the system? Also, while you can generate tools to run outside of Claude, there is definitely a strong incentive for non-developers to just create apps that run inside it. This paves the way for future enshittification of these products and I would like to understand how we could prevent this.

Finally, and that is what concerns me the most, is the possibility of losing that “meta” learning process that characterized my first round of PowerBrowsing experiments, that is, learning the methodology and the tools to solve a whole class of similar problems. This was so valuable to me that I am worried about missing it if we have an LLM building everything for us. My current assumption is that there will likely be a new, different meta-learning process that involves AI tools, but then I would like to make sure that is one we can rely on, something free (as in freedom from any particular service), fair (as it does not privilege just a few), and open (as it can be easily be taught and shared with other people).

What next?

I am fully aware I just scratched the surface of what “vibe reversing” could be. Just so you know, this document was originally a section of another post I was writing, which you might expect sometime soon(ish) in one or more likely more “episodes”. In part as a teaser for you and in part as a commitment for me, here is what I was planning to write about:

- how current LLM-powered services are not just bare models anymore, but rather a mix of models and tools that make the gap between self-served models and LLM services wider and wider

- how that leads to so many chances for enshittification that in a few years you’ll miss how things were going in 2025 (you already caught a glimpse of that in this very post)

- what we can do now, with local models and open frameworks, to create something that works for us (and the advantages of owning this technology)

- how we can use these tools to break free from other systems that try to lock us in

In the meantime… find your own problem and have fun vibe-reversing it :-)